A good man died today.

My Uncle Loren died today.

I just saw him last week in the Midwest, and we played cards together. I fetched him a wine cooler from the garage because he didn't want all the alcohol from a regular beer, and I slid it into a can cozy in front of him, on the dining room table. The next day, before Aunt Shirley and Uncle Loren left, Uncle Loren and I both ordered the same thing at the pancake house: honey wheat pancakes with syrup. I gave him part of my butter because the waitress didn't bring him any at first. "They're good, ain't they?" he asked me, about a fourth of the way through them.

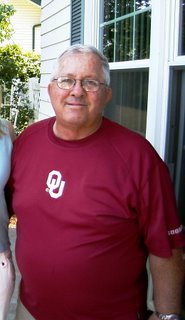

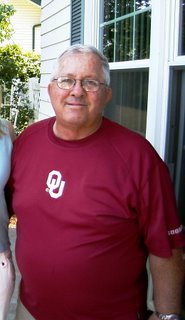

Uncle Loren is -- was...I'll never get used to referring to him in the past tense -- short and round, with a round face and round head. His skin was bronzed and a little leathery from checking Oklahoma oil wells for years. That was his job, and he got the biggest bonus this year because he did his job better than anyone else. He was prone to wearing a crimson Oklahoma University T-shirt with gray sweatshirt-material shorts and sneakers unless we were in church. I remember him wearing suits to services and singing hymns with vigor, but that was years ago, when I still lived down south, where I was born and lived until I was nine.

Uncle Loren was fiercely conservative and fiercely Christian. I learned not to talk politics with him after I began college. "This separation of church and state is bullshit," he'd say, or something like it. He liked to hunt. He sometimes began sentences with, "Well, hell!..." Uncle Loren was a guy's guy, a straight-edge "son of a buck" (he loved that phrase). But Uncle Loren had a soft side that was as steadfast as his morals. He loved peanut-butter chocolate milkshakes from Braums, big plates of my mom's spaghetti, and Louis L'Amour western novels. Or any western novels. And he loved me and my two sisters.

He was there when I was a baby, and he was there as I was growing up. He gave me bucking-bronco piggyback rides as my sisters and I giggled and egged him on. He was a jokester, and he loved to make us laugh. He'd hide our dessert at dinner when we weren't looking, until we'd figure it out and yell, "Heeeeeyyyy!" He brought out our wit, even when we were young girls. He was there in the stands at my elementary-school softball games, cheering me on. When I was nine, Uncle Loren would take me out in his Datsun pickup to collect soda dn beer cans from farm roads. When we'd spot a few, we'd both jump out -- me in my little navy windbreaker -- and put them in a garbage bag. When we cashed them in back in town, we'd split the money. But I think Uncle Loren probably gave me more than my share.

He came to the Midwest in time for him and Aunt Shirley to buy me my first prom dress -- a black velvet off-the-shoulder discount number. He knew how to make me feel beautiful. "Your butt looks good, too," he said as I spun in the dress. He smiled and looked off into the distance. I remember him saying that because it might sound odd to anyone else, but it was probably the only compliment I got from a guy that year. Every time he saw me, he'd tell me I looked good. He made me feel beautiful. I could always count on that. If he had a seat between one of my sisters and me, he'd say, "And I get to sit between two good-lookin' girls."

He loved my Aunt Shirley. You could tell just by the way they looked at each other. He'd pinch her sometimes when she wasn't looking and make her squeal and laugh. "Loren!" she'd say, pretending to be appalled.

He used to wrangle cattle on Oklahoma farms. And he used to be in the Army. He loved that I'm strong for a girl. He told me once that push-ups are the one exercise that will strengthen your whole body. For that reason, I do at least 30 every time I go to the gym.

He used to chew tobacco and spit it into a Solo cup. He used to wear cowboy boots. He liked to get a toothpick from the dispensers at diners as he paid his bill and leave it in his mouth as he walked out to the car. I used to mimic him sometimes, getting a toothpick of my own. His knees got bad later. He gained more weight than they could handle, and he had to have surgery on them. He started moving slowly. He couldn't walk very far or very fast. He'd hobble along next to you, but he thought he would recover, gain strength, and get better.

The last time I saw him, we talked about New York. "I don't know how you live among all them people," he said, sitting back in his chair and laughing. Aunt Shirley chimed in: "The only way you'll get him out there, Newbie, is if you get married out there." I laughed at all of it. "We'll take you to Central Park, Uncle Loren. You'll like it there."

Uncle Loren never had much use for beaches, either. He and Aunt Shirley went to Mexico with their daughter and her family, and he was so bored he'd take long walks on the beach with his grandson at 6 a.m. to pass the time. "I'd rather be on a ranch and look at all the cattle," he said last week, motioning with his hand in a way that made me think he was seeing them right then.

I'm not even engaged yet. But on the day I get married in New York, I'll look at Aunt Shirley sitting by herself in the church pew, and I will try not to cry. But then I'll picture Uncle Loren in Central Park, sitting on a bench, looking at "all them people," and wishing he were on a ranch, looking at all the heifers and the steers and thinking about his niece, all grown up and here, in the big city.

So, by the grace of God, I went tonight, and it was fantastic. I've never been to a big-production concert before. I like smaller venues where the unwashed masses aren't constantly stepping on your shoes. But Madonna's setup was great: the dancers were amazing, the video screens were huge and plentiful, and the costumes were understated and beautiful. I ate up the Saturday Night Fever riff during "Music," and I friggin' loved the Ring-esque quasi-creepy horse theme at the beginning. Because this is not that serious, people, no matter what Madge and her crucifixion/Bible-quoting/AIDS-in-Africa montages would have you believe. It's just damn good entertainment, and Americans will pay top dollar for that.

So, by the grace of God, I went tonight, and it was fantastic. I've never been to a big-production concert before. I like smaller venues where the unwashed masses aren't constantly stepping on your shoes. But Madonna's setup was great: the dancers were amazing, the video screens were huge and plentiful, and the costumes were understated and beautiful. I ate up the Saturday Night Fever riff during "Music," and I friggin' loved the Ring-esque quasi-creepy horse theme at the beginning. Because this is not that serious, people, no matter what Madge and her crucifixion/Bible-quoting/AIDS-in-Africa montages would have you believe. It's just damn good entertainment, and Americans will pay top dollar for that.